Amba Sayal-Bennett works across drawing, projection, and sculptural installation. Her practice explores performative dynamics within human and non-human assemblages, from our use of language to material encounters in the studio.

Amba Sayal-Bennett lives and works in London. She received her BFA from Oxford University and her MA in Sculpture from The Royal College of Art. She was awarded her PhD in Art Practice and Learning from Goldsmiths and has published her practice-based research with Tate Papers. Amba is a co-founder of Cypher Billboard, an artist-run public program of site-specific billboard artworks and off-site projects based in London.

ASB, Reservoir of Many, powder coated mild steel, magnets, 47 x 43 x 22cm, 2020

You use your creative practice to experiment with the doubling of forms to consider how repetition can be an industrial and mechanised act, as well as meditative, ritualistic and performative. How do you use your practice to marry the two?

I think these different aspects relate to an interest in emergence within my practice. Machinic processes always involve some sort of exchange, so although the process itself may repeat there is a possibility for variation in form.

Clean lines and clinical shades often define your work, yet it feels as if there are references to the human form and biology also?

This human-technological hybridity exists at a methodological level. Whether I’m using stencils in my drawings on paper, or computer modelling software to design my sculptural works, my body is always working in conjunction with material or technological apparatus. I’m interested in how these tools, rather than being passive, have agency within the work. I’ve come to think of my practice as a cybernetic system that evolves through a process of human-material engagement and feedback. The works in the studio therefore emerge from a hybrid agency that is composed of both human and non-human elements.

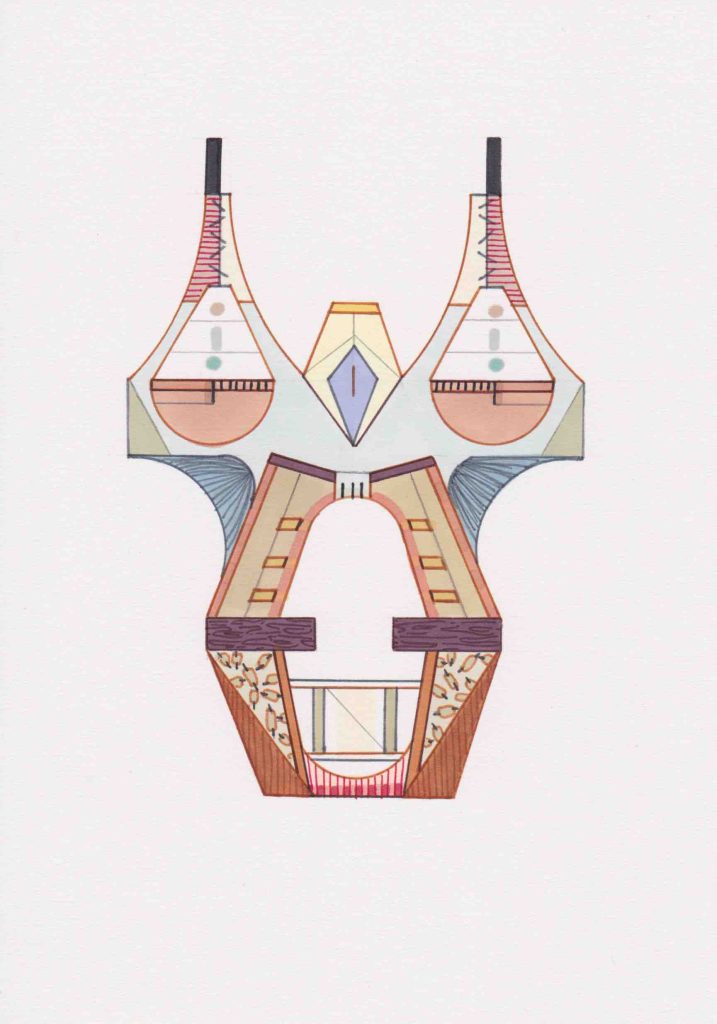

ASB, Installation view 1, A Mechanised Thought, indigo madder, 2020

I read that you view drawing as a medium which is directed towards the future. Can you tell me more?

The language of plans, diagrams and maps, drawing has an endless potential for use. As an opening up or sketching out, drawing is always directed towards the future. This is part of its inherent incompleteness. I’m fascinated by working drawings such as scores or notation, ways to both record and instruct action. Before computer aided design, hand drawn technical drawings would present different stages of a process at once, creating a collapsed chronology. In this way, drawing has an elastic relationship to time: a relationship to the present through the indexical mark, to the past as a record of an action, and to the future through this potential for translation and use.

What is the relationship between your drawings and larger scale sculptural work?

I have always used translation as a method in my practice, transposing drawn forms across different media through large-scale projection installation and within my sculptural works. I only started working with metal three years ago. Within the context of my expanded drawing practice, metal has a strong relationship to paper, as a sheet material it bends and folds and through welding or slotting it can move between two and three dimensions almost instantaneously. Within my metal sculptures there is an implied flatness to the work which connects it to processes of testing and modelling.

Can you tell me how Lockdown was for you and your creative practice?

Each lockdown has been very different. The initial lockdown in March 2020 began as I was working towards my degree show at the Royal College of Art. With no studio or workshop access, my practice had to adapt, and I focused on reading, drawing, and developing my digital skills. The sculptural metal work that I made during this time also shifted from incorporating welding and soldering, to using different bonding techniques such as slotting mechanisms which meant that the work could be assembled outside of the workshop.

Amba Sayal-Bennett, Conte, 2018

Any exciting projects or shows coming up?

I am very excited to be going to Italy for three months in January for the Derek Hill Scholarship at the British School at Rome. I’ll be exploring concrete legacies within the city through a speculative drawing practice. In particular, the recursive nature of this material and its repetition and variation in classical, rationalist and brutalist architecture such as the treehouse ruin of Giuseppe Perugini, a non-static, modular system designed to be recomposed. Using a linear logic, I’m going to use walking as an embodied method to trace concrete enunciations that create a certain cadence and rhythm within the city. The body of work that I make will form a personal archive of these encounters, a synchronic exploration of concrete features within Rome.