Varvara Keidan Shavrova is a visual artist, curator, educator and researcher. Born in the USSR, she lives and works between London, Dublin, and Berlin. She studied at the Moscow State University of Printing Arts, received her MFA from Goldsmiths, University of London, and has been awarded Arts & Humanities Research Council Studentship by London Arts & Humanities Partnership, to conduct her practice-based PhD at the Royal College of Art in London. She has exhibited internationally, including at the Venice Biennale of Architecture, Gallery of Photography Ireland, Moscow Museum of Modern Art, Espacio Cultural El Tanque, Tenerife. Shavrova curated international visual arts projects, including The Sea is the Limit at York Art Gallery (2018) and Virginia Commonwealth University, Qatar (2019), and co-curated Beijing Map Games: Dynamics of Change , an international art and architecture exhibition in Beijing (China), Birmingham (UK) and Terni (Italy). She is the recipient of the National Lottery Arts Council of England Project Awards (2019-2020 and 2020-2021), the Arts Council Ireland Visual Arts Bursary Award (2021), and the Prince’s Trust Individual Artist’s Award, among others. Her work is included in a number of public and private collections worldwide, including at the Department of the Foreign Affairs and Trade of Ireland, at the Office of Public Works art collection in Dublin, at the Ballinglen Arts Foundation collection in County Mayo, and at the Museum of the History of St.Petersburg in Russia. Shavrova is represented by Patrick Heide Contemporary Art, London.

This audio interview was recorded online on 29 September 2021 and then transcribed

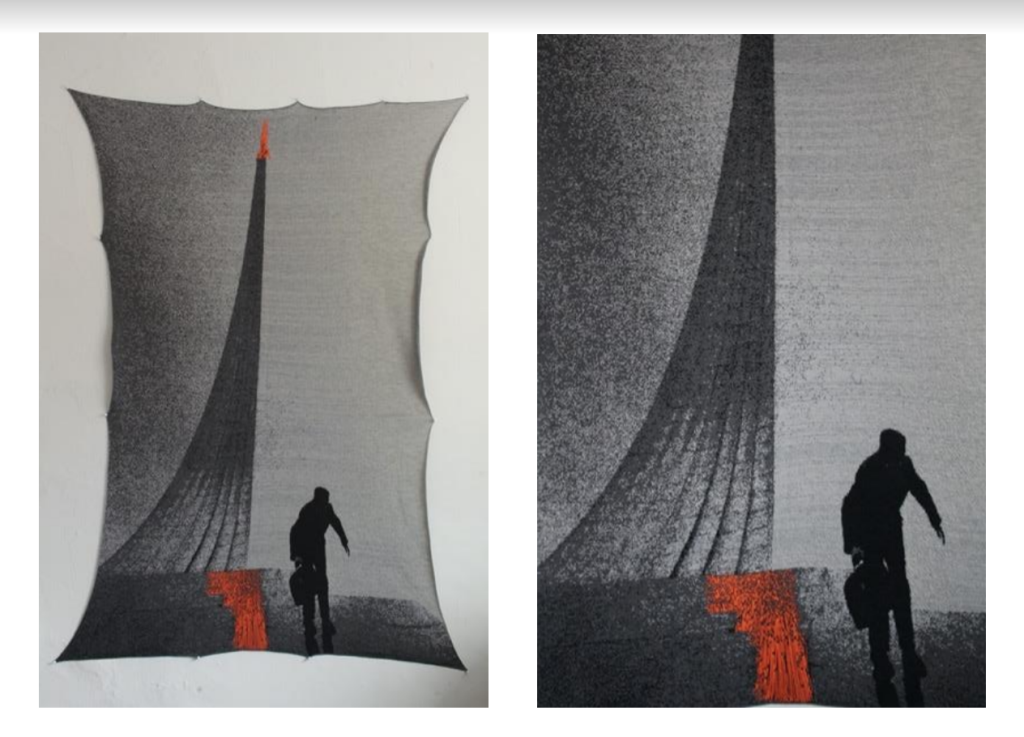

The Palace of The Soviets and King Kong, 2020, Digital knitting, hand stitching and embroidery, wool and synthetic thread, 122 cm x 255 cm

You are both an artist and curator, how do these two practices intertwine?

I think for me, what is interesting is my knowledge as an artist and how I can include it in my curatorial practice. My main position as an artist/curator is to always put the interests of the artists first, not my own curatorial interest. Of course, I collaborate with artists, but I do not (at least I try not to) impose my own will entirely, like some curators might choose to. And also, just from a practical point of view, I really try to get the best deal for the artists. I always defend the necessity for artists to be paid a fee. If I’m curating an institutional exhibition and if the artists have placed some specific and reasonable requirements, I try to meet those needs. For example, creating a dark room for a video piece or building a certain configuration of a plinth or display work in a particular area, or offering certain lighting. So, practical things that are actually incredibly important for individual artists and also in the context of group exhibitions. Ultimately, I try to accommodate and have a discourse and collaborative discussion with artists regarding how the work is presented, how it is perceived, how it is read potentially by the visitors, and also by the institutions. The practice of being an artist and curator means that, as I say, I put the artists’ interests first and not the curatorial ego.

Monument to Cosmos, 2020, Digital knitting, hand stitching and embroidery, wool and synthetic thread 100cm x 178cm (detail of image of the right)

Where did you spend lockdown and how did it impact your creativity?

During the lockdown, I was in two places, first in Dublin, and later in Berlin. The lockdowns in Ireland were very strict. We had huge limitations on how far we could go outside from our house (two kilometres to start with, that lasted for four months). The second lockdown was imposed in November 2020 and lasted until I left Dublin in early April 2021 when I moved to Berlin for a residency. During this time we were restricted to operate within five kilometres from our house. This was hard because my studio is fourteen kilometres away and even cyclists, who were in slightly less danger of being stopped by the police, were still regularly stopped, and of course, when the weather was bad or I had to carry things, I drove to my studio. This meant I had to invent reasons for going there. This impacted my creativity in the sense that I actually didn’t have a place to work and I lived in a small cramped apartment with family members and two animals, and it just was chaotic. I found the first few months of the lockdown probably the toughest. During that time, I applied and was awarded an emergency grant offered by the Irish arts council that allowed me to justify making work because all paid work stopped on the 20th of March 2020. In fact, my last paid job was in Irish prisons which was very interesting and very satisfying but that stopped and actually, to this day, I haven’t had paid work in a proper sense of the word, and have therefore relied entirely on grants from different foundations, but primarily from the arts councils. Therefore, I think the financial limitations and the restrictions were quite significant during the lockdowns.

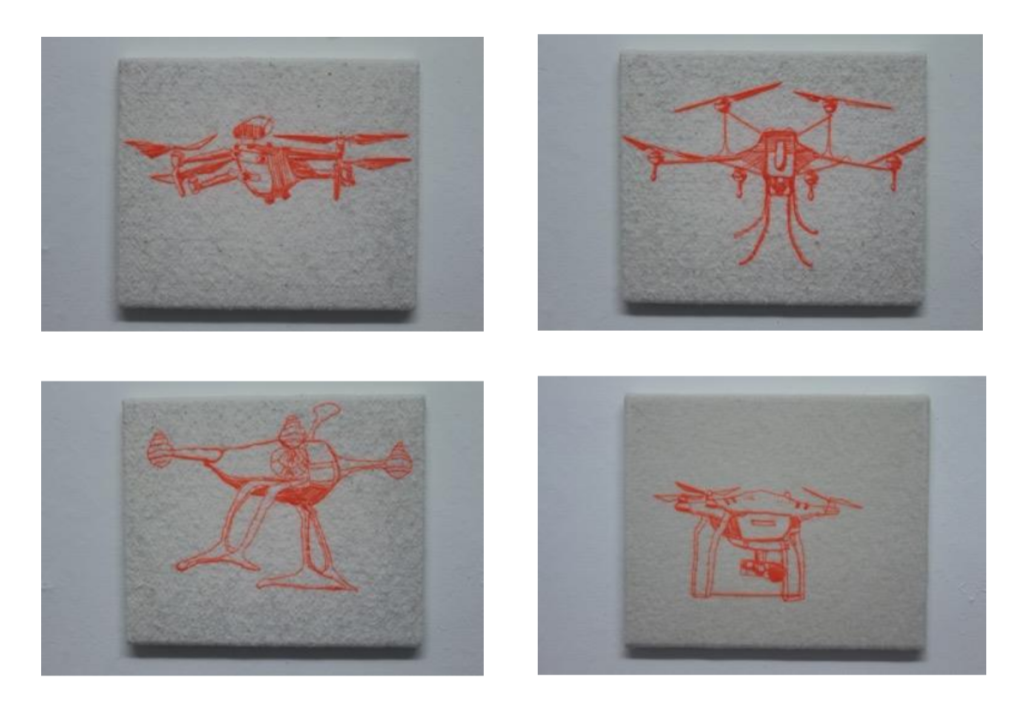

It was disappointing but also I think the lack of conversation, the lack of a studio environment for practitioners like me was very drastic. So, when I got the arts council grant, I made small works because they were portable, I could actually make them in the studio, bring them back and fourth on the bicycle. I started making small textile and fibre-based pieces which developed into a nice body of work that contributed to the threads of the surveillance project that I continued working on whilst I was in Berlin, and that I’m still working on today. The works are ‘embroidered drawings’, as I call them, sort of freehand embroidery, featuring drones: both domestic or lay use drones, and military drones.

If you could teleport yourself to any time or place, where would it be?

I think a lot of my work refers to Russian and Soviet avant-garde, so I would be really curious to be teleported to Rodchenko and Stepanova’s studio, in Moscow in the 1920s. I’d love to be a fly on the wall, observing their collaboration as people and as artists at this incredible time. This period that especially interests me would have been between 1911 – 1935 in the Soviet Russia. It would be very interesting for me to observe artists like them and also the likes of Vladimir Tatlin and others who worked on ideas of building the brave new world and correlating their ideas of the revolution with the dreamworlds of flight. Also, anywhere on the warm sea right now would be great: it’s already getting quite cold! So, somewhere like Cyprus or Majorca would be ideal!

Soft Drones, 2020, Hand stitching and embroidery, 25cm x 30cm each

After graduating from an MFA at Goldsmiths, you have been recently awarded a partnership to conduct a practice-based Ph.D. at the RCA, can you talk a bit about your research area and interest?

My research proposal for this studentship drew directly on my thesis that was part of my MFA at Goldsmith’s, which dealt with flight and representation of flight and nostalgia during the Soviet Union era. My PhD research title is ‘Dreamworlds of flight in the age of surveillance capitalism,’ which, of course, might change because the PhD structures and the way they grow and develop are quite different from Master’s thesis, in that you go much deeper into your research. However, those themes of flight and the notion of flying machines, space exploration, flight exploration, have both a historical and contemporary interest for me. I enjoy juxtaposing or looking at flight through the lens of current exploration of space vis-a-vis exportation of capitalism, extraction, and coloniality, all projected into the planetary world. So, I guess it’s expanding in that direction and I think it’s quite political. I’m also looking at new modes of societal buildings and options that we, as artists, might be able to present: as positions, as theories, and also as potential ways of living. I am looking at the role of artists today, not only as visual creators, but also looking at the positions that the artists assumed during the Soviet avant-garde era: artists as engineers, scientists, and also ‘societal engineers’, if you like. I’m looking at the role of the artist and at the role of labour in the studio environment. As a woman, I’m working with materials that I associate with women’s work, women’s labour, textiles, fiber-based materials. I’m going to also look at labour and its trajectory historically, and at the value of labour and the value of the studio work within the artistic practice.

Your practice focuses on excavating the layers of history through the process of remembering, recalling, retracing, and re-enacting stories. Where did your new body of work “Threads of Surveillance” stem from?

I think I touched upon that a little bit earlier and I would say that it did grow directly from that investigation of flight and looking at flight as surveillance mechanisms. I am also looking at surveillance that is not only external, for example, represented by drones, which is the body of work I mentioned earlier. I am also working on the investigation and the way that we can visualise, interpret and present surveillance that is actually invisible and that is, of course, a huge challenge because how can we represent the invisible? How can we tangibly create or describe something that is in our phones or in our computers i.e digital surveillance? I think my work is going to develop in this direction by trying to net the invisible and to catch the impossible, which, yes, probably is quite a mad idea. But, interesting all the same.

Mapping Fates, 2017, Hand-loomed jacquard tapestries, wool, silk, thread, photographs, objects, sound, Vladimir Lenin’s apartment, installation view, Facts and Fictions ProArte14 festival of contemporary art in traditional museums, St. Petersburg

“Inna’s Dream” came out of your Goldsmiths MFA Degree show in 2019 but was exhibited a number of times in different contexts. How does the work relate to your family history through memory, nostalgia, and reflection?

Yes, the works from ‘Inna’s Dream’ series, essentially, are based on chapters from my family history. It deals with the story of my great uncle who was a well-known Soviet engineer and aeroplane designer. He designed and built the first Soviet amphibious biplane Shavrov 2, actually in his apartment, in Petrograd (modern-day Saint Petersburg). Because he was an inventor and there wasn’t such a thing as the flying boat in the 1920s Soviet Union, he decided to design and to build it, and he did so with his own hands and with the help from another mechanical engineer. They literally built the machine in parts in his apartment, it was lowered out of the window, assembled outside, taken to an aerodrome, and then my grandfather, who was the engineer’s brother, and a military pilot, test flew the amphibious plane. Once it passed the tests, SH-2 was officially commissioned by the Soviet government. It was flown during the Second World War, it was a spy plane, an ambulance plane, an exploration plane that took part in a famous expedition to the Arctic in 1934, led by explorer/captain Otto Schmidt. Schmidt’s ill-fated expedition set off to the Arctic in the midst of winter, got trapped in the ice and then the boat sank, not unlike Titanic, except all the members of the crew managed to get off the boat and survived. And on that boat, together with passengers, was the SH-2 amphibious plane which then also drifted with the crew for two months until they were rescued and the machine took part in the rescue operation. So for me, it is not only a very famous story but also a symbol of an amazing dream that was realised by this relative of mine, an inventor. In my own work, I tend to subverted those elements of masculinity and power and violence, and I recreated the machine in carpet, which I hand-tufted during my MFA course in Goldsmith’s. It took a year and a half to make this installation. I have presented it almost like a model aeroplane lying on the floor. It is so huge, it’s about seven metres by five and a half metres and it is quite an accurate replica of the aeroplane made on the basis of the original drawings by my great uncle. This work obviously deals with those elements that you mentioned in your question: memory, nostalgia, and reflection presented through the woman’s eye, and through the feminist perspective. It addresses the questions of labour, of artmaking and also, of the purpose that lies behind the objects that you make.

Inna’s Dream, 2019, Hand tufted Axminster wool, hessian canvas backing, thread, relief print, and acrylic drawings

7 metres by 5.5 metres by 3 metres. Installation at Patrick Heide Contemporary Art London

What have you been working on lately?

My most recent work is a continuity of, Inna’s Dream, the SH-2 aeroplane project, and threads of surveillance, the drones project. My most recent work entails collaborating with a manufacturer based in Venice and right now I’m just doing tests with them making images of drones in velvet, which is very tactile, and is again associated with all kinds of domestic things like upholstery and furniture. I am also developing a new body of work which includes a knitted parachute that I have partly made in collaboration with a knitter in Berlin. The parachute itself is an interesting template because it’s based on the parachute that landed Rover on Mars, and it contains a coded message which scientists chose to put on the parachute that they sent out into space. My parachute, therefore reinterprets the original message, the design and the colours of the Mars Rover parachute, including the coded message which says, ‘Dare Mighty Things’. It is interesting for me, when the scientists border on the absurd and decide to send coded messages – but to who? To outer space. Fascinating. So, my parachute, like my flying carpet, like my aeroplane is not going to save anybody’s life, it’s made from merino wool, it’s very gorgeous to touch and I’m planning to embroider it with drones and it will be presented, hopefully, in a group show called ‘Haptic Codes’ that I am co-curating in New York and in London in 2022.

Dare Mighty Things, The Parachute Project, Work in progress, Berlin 2021